Month: March 2020

Vickers Wellington Mk III – Progress report… A little more progress

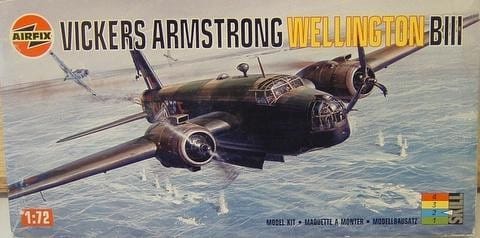

Airfix has to be commended for its tribute to 425 Alouette squadron with its first model kit of the Wellington.

Airfix has come a long way since the late 50s when it made the Wellington Mk III.

My next build will be Trumpeter’s 1/72 scale Vickers Wellington Mk X for my friend James who I am dying to tell you what he did a few years ago as a tribute to 425 Alouette squadron.

He wants me to take pictures of the steps while I am building it.

I will have to finish up the Mk III before, and it is not that easy especially trying to mate the engine nacelles with the wings unless you don’t mind if plastic cement is oozing out all over.

The upper parts of both nacelles don’t mate perfectly with the top and the bottom wings. I had tried glueing the bottom parts first, but it did not work out.

So I had to unglue everything and then I used super glue at the wing roots. It did not work well either…

So I had to ask Mother Invention who told me…

Use a Vise-Grip…!

Vickers Wellington Mk III – Progress report… Even more history about 425 Alouette Squadron

I could go on an on with the history of 425 Alouette… This I had written a few years ago about one member of the ground crew. It was about Corporal Lupien.

An official RCAF photo but with the wrong caption!

[Photo PL18351] records the top left [ground crew LAC C. Schierer] four aircrew and bottom ground crew – L to R LAC E. Merry, Cpl. A. Lupien and LAC Y. Monette. These were the very proud ground crew who painted the impressive record of 46 operations [32 night and 14 day] plus the little « Turtle with Wings » nose art.

Corporal Lupien isn’t where the caption says he is.

Clarence Simonsen told the story of Wellington Mk X Turtle with Wings. (be sure to click on the link)

Corporal Lupien is also seen on these photos taken at Tholthorpe in 1944.

And also here in Montreal 16 November 1946!

Vickers Wellington Mk III – Progress report… More history about 425 Alouette Squadron

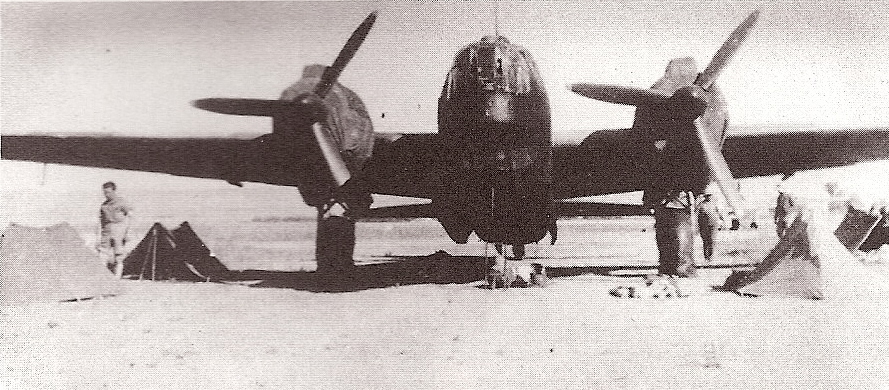

This is KW-W at Dishforth most probably before 425 Squadron will leave for North Africa in 1943. We can see the air filter on top of the right engine. So I figure this is a Wellington Mk X and not a Mk III.

Collection Réal St-Amour courtesy Chantal St-Amour

That photo was part of Réal St-Amour’s collection. Réal St-Amour was the Alouette’s adjutant from 1944 to 1945.

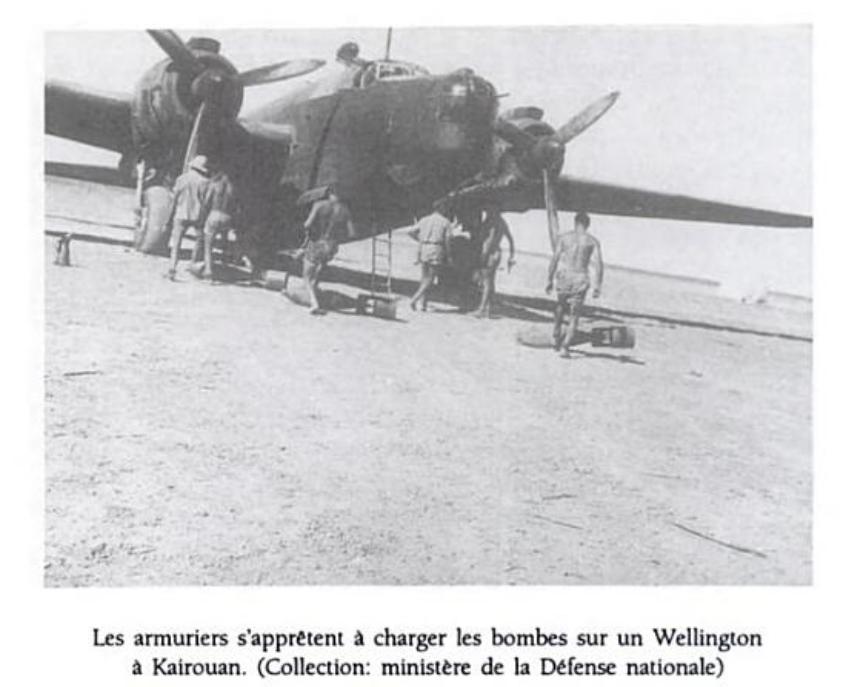

These next photos are from the collection of Roly Leblanc, courtesy of his son Michael. Michael had shared them back in 2011. His father was a ground crew and he took lots of pictures of Kairouan.

We have a good idea of how were the living conditions for Roly Leblanc in North Africa in 1943.

This was taken from Gabriel Taschereau’s memoirs

“At noontime, the thermometer reached 130 ° F and even 140 ° F… “

Group Captain Gabriel Taschereau, D.F.C., C.D., A.D.C.

All crews were equipped with new aircraft, Wellington Mk Xs, especially adapted to face the tropical climate. After a remarkable war effort during its stay in Dishforth, Yorkshire, 425 Squadron was transferred to North Africa in the spring of 1943 to write the second chapter of its brilliant epic.

With few exceptions, airmen who already had more than twenty bombing missions to their credit were assigned to other Canadian squadrons residing in England. Those who insisted on following their squadron to Africa were informed that they would have to complete at least twenty other raids before being repatriated. This was the case for many.

Shortly before the big departure, the two deputy commanders, squadron leaders Georges Roy and Logan Savard, were promoted to the rank of Wing Commander and each were appointed to head a new squadron. All the crews equipped Wellington Mk Xs would be assigned in Tunisia, a desert location about thirty miles southwest of Kairouan, between two Arab villages called Pavillier and Ben-Zina.

Collection Roly Leblanc courtesy Michael Leblanc

The journey was made in several stages: Dishforth, Portreath, Gibraltar, Fez (Morocco), Telergma (Algeria), and finally the new base named Pavillier-Zina. From that time on, 425 Squadron became part of 331 Wing, part of the 205 Group of the North-West African Strategical Air Force.

This arrival on foreign soil was not without some inconvenience: no vegetation, no buildings; therefore, no shade to protect oneself from the rays of a blazing sun; sand and dust; flies, scorpions, tarantulas and mosquitoes.

Collection Roly Leblanc courtesy Michael Leblanc

These last insects being carriers of malaria, we had to swallow one quinine tablet per day, as a preventive measure. Moreover, as water is a scarce commodity, it was distributed sparingly, especially since it had to be collected in a tanker truck from a well located about ten kilometres from the camp. And one day, the attendants of this service came back empty-handed, mentioning that the well was dry, and that the body of an old mule had been discovered at the bottom.

Gone are the relative luxury of Dishforth’s mess, with its clean rooms and pleasant mess the facilities in Kairouan were rather rudimentary.

Collection Roly Leblanc courtesy Michael Leblanc

Nevertheless, the morale of the troops remained high. Enthusiasm reigned at all levels. Under the command of the wing commander Bill St-Pierre, and his new deputies, the leading squadron leaders Claude Hébert and Baxter Richer, air operations against the enemy resumed more successfully, but under radically different conditions than those we had experienced at Dishforth. German fighters were still on the lookout, but were fewer in number; the A.A. guns and less threatening beams of spotlights. And we no longer had to face the formidable enemy that was icing. On the other hand, our engines often tended to heat up, which was not very reassuring.

In terms of comfort, it was neither the Ritz nor the Savoy. No more the relative luxury of Dishforth’s mess, with its clean rooms and well-stocked dining room; absent, the kind and dedicated “batwomen”, the angels of the W.A.A.F.; become chimeric the “pubcrawling” tours to Ripon Boroughbridge, Harrogate and York.

Collection Roly Leblanc courtesy Michael Leblanc

If the evening and night brought us a diversion in the form of bombing missions, the day, however, seemed endless. The only place we could relax a little was in the shade of our aircraft wings, because in our tents the heat was simply stifling. At lunchtime, the thermometer reached 130° and even 140° Fahrenheit, which allowed us to easily cook an occasional egg on a sheet of metal exposed to the sun. Another cause for celebration: the menu. At breakfast, we had “corned beef”; at lunch, more “corned beef”; and in the evening, to make a change always from “corned beef”.

Collection Roly Leblanc courtesy Michael Leblanc

To compensate for this lack of diet, some crews, during their N.F.T. (daily test flight), managed to simulate an engine failure near a U.S. Air Force base at lunchtime. We were then invited by our American colleagues to share their feast: a four-course meal, with beer, tea, coffee, fresh lemonade, ice cream, etc., etc. Thus, well fed and our engines rested, we took off again to return to our base, filled with the euphoric optimism of our twenties.

Our military objectives varied with the advance of infantry forces. Before the landing on July 9, we attacked by night the aerodromes of Catania, Messina and Gerbini, the fortified squares such as Sciacca and Enna, as well as the banks of the Strait of Messina. Later, after the invasion itself, our targets gradually moved up along the Italian boot. Thus, Reggio, Naples, Capodichino, Salerno, Scaletta, Avellino, Montecorvino, Aversa, Formia, Grazziani, Cerveteri and many other towns, seaports or yards were repeatedly attacked by the 425 Squadron Wellingtons.

Collection Roly Leblanc courtesy Michael Leblanc

The successes achieved by aircrew were largely the result of the close collaboration between “pigeons” and “penguins”. All these brave mechanics, gunsmiths, electricians, drivers, technicians of all kinds, under the expert guidance of flight Lieutenant Hilaire Roberge, never spared their time or effort to make sure the impeccable maintenance of the aircraft entrusted to them.

Collection Roly Leblanc courtesy Michael Leblanc

The administrative services, under the skilful direction of flight lieutenant Edmond Danis, were also always impeccable. Despite our isolation, and the difficulties of communication, our friendly Warrant Officer has constantly managed to manoeuvre to make sure the smooth running of the squadron’s machinery.

On the spiritual side, it was our devoted padre, Father Maurice Laplante, who was very successful in ensuring divine protection on his swarthy flock. He celebrated daily mass in the shelter of a “marquise”, and regularly blessed the planes leaving for their destiny.

Regarding the physical health of our troops, we have nothing but praise for our medical service. This service was run by Dr. Hector Payette, the “little doc”, who, despite his small size, has always been able to rise to the occasion. He was the one who managed to cure us of dysentery that affected us all at first, by feeding us castor oil through a funnel placed in his patients’ mouths. He was also responsible for administering quinine and atabrine tablets for malaria, and “mottons” of salt to combat water loss through sweat. And how many cases of sunstroke has he been called upon to treat! Not to mention the care of the wounded, as was the case for Sergeant Léon Roberge, a wireless operator who returned from a raid with a shrapnel in his thigh and machine gun bullets in his calves, following an unexpected encounter with a Junkers 88.

After a six-month stay under the burning sky of southern Tunisia, the squadron returned to England. But before we could enjoy a well-deserved vacation, we had to undergo a delousing cure in a hospital in West Kirby, to get rid of the sand fleas brought back from Africa, which had made their home between the dermis and the epidermis of each of us.

Most of the “navigators” were later directed to the O.T.U. (operational training schools) to serve as instructors, sharing their experience and knowledge with fresh crews from Canada. These new crews, once their internship in O.T.U. was completed, joined the sedentary services already installed at their new base in Tholthorpe, to begin the third phase of the epic history of 425 Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

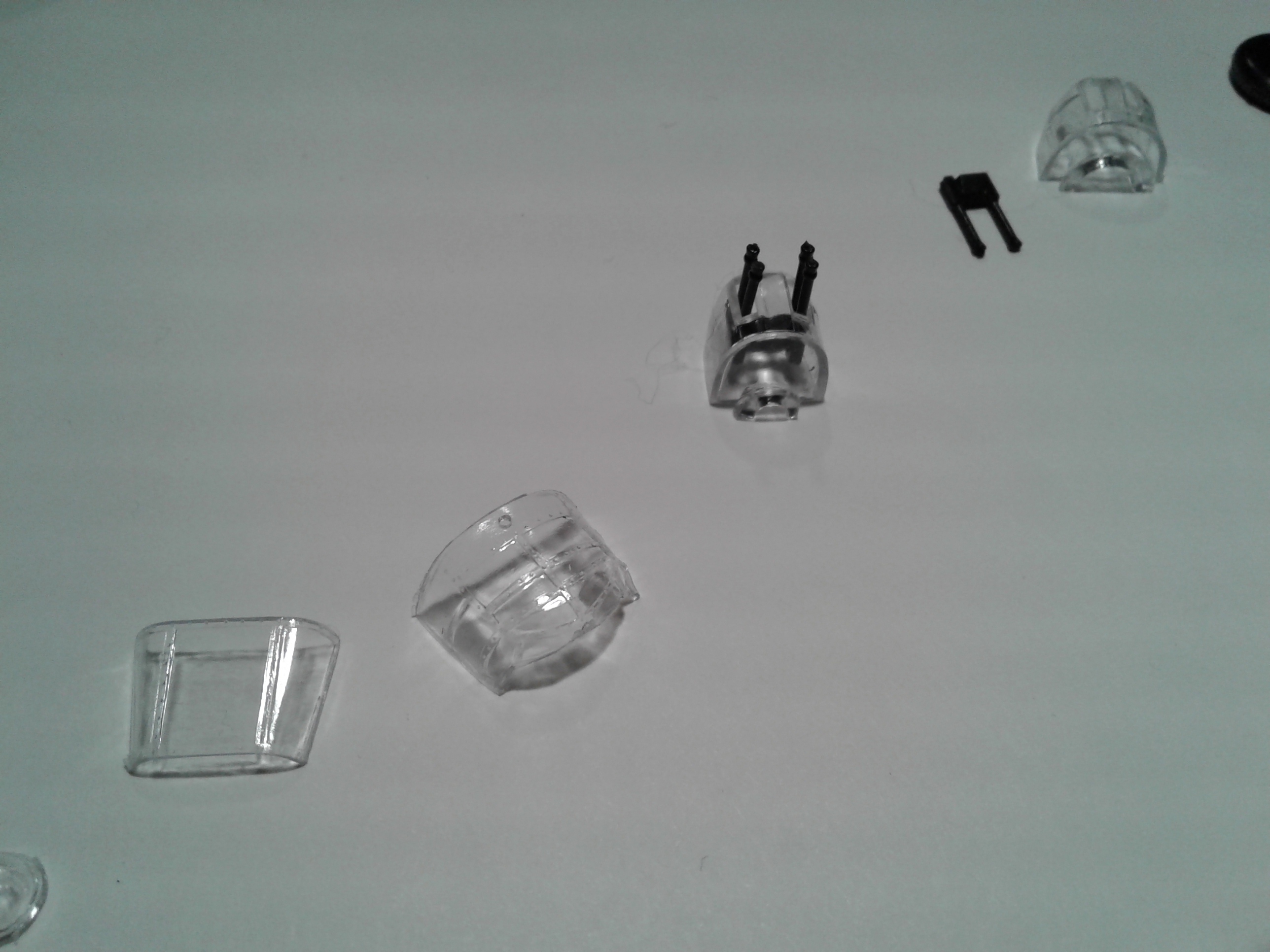

Vickers Wellington Mk III – Progress report

I have been working just a little on the Airfix Wellington Mk III since I had lots of translation work to do.

I have started painting a base coat on some parts, but there is not much information on how to paint the interior and not much details to be shown later.

I have searched for information on how to paint the interior and found these links helpful.

http://www.olddogsplanes.com/wellington.html

What I make of this is not to bother that much about the interior and to proceed faster with building the Wellington. I have added a touch of paint to the figurines.

I will add more later this week.

Intermission – Some useful tips from MP

I have started procrastinating with my next build.

Airfix classic old Wimpy is not a shake and bake model kit. I am being very cautious since I am building it for James who is a filmmaker I met in 2015. How that meeting evolved will be a subject for another post.

This is where I am at right now with my build.

Last night I was thinking of going back to work on my slow progress, but I went instead on this blog and found some useful tips on weathering your model kits.

It’s worth reading and I must remember to use these tips…

https://mpminiatures.wordpress.com/2020/02/20/eurofighter-typhoon-fgr-4-1144-scale-part-2/

Airfix Wellington Mk III – Remembering Charles Andrew Reist

I will convert the old Airfix Mk III to an Mk X in homage to this young airman. I wrote this in 2018 on my blog RCAF Alouettes II. It was the second blog about that squadron having used all my free 3 gigabyte downloads on WordPress.

That series of posts about this young man will be all the motivation I need to build this.

This was the first post.

Charles Andrew Reist

Charles Andrew Reist was part of the Alouette Squadron, but not for long. His story will be told by using his service record file.

I did not know Charles Andrew Reist was a member of the Alouettes before his niece wrote this comment…

Hello sorry but I don’t read French. However, my Uncle, Charles was a Sergeant BA 425 Squadron R/163707. He died August 7th, 1943 in World War II. I would like to get pictures of him and his Squadron. Is their any of his Squadron alive. I would love to sent them a note and see if they recall him. His medals, any documentation that I can have copies of. I am doing this in his honor and for my family. I do hope you can help me. Thank you so much. My name is Frances Preston.

I was quite curious to learn more about her uncle so I asked her to give me further details…

What was your uncle’s full name? I will be glad to help.

The reply came quickly…

Hello Pierre, I am sorry forgetting to add his full name. Sgt. Charles Andrew Reist Thank you so very much this really means a lot to me. I never got to meet him but he gave his sister a beautiful silk blanket and pillow for her first girl she had, and I am her. Also as child I was always very sensitive to Remembrance Day. Later my mom told me why.

Pierre again anything you can help me with it I will be so grateful.

Frances Preston

You now understand why I will help Frances learn more about her uncle, who was a rear gunner, and his crew who were killed flying Vickers Wellington Mark X, code KW-R.

Intermission – A classic

Next build – Trumpeter Wellington Mk X

The Trumpeter Wellington Mk X I am building for James will have KW-K markings (Serial # HE268) to commemorate the only 425 Alouette Squadron Wellington to be downed by a German fighter while on its way to North Africa in 1943.

There is a YouTube review of the Wellington Mk III which is quite similar to the Mk X.

As always there will be more on this story…